If you’re new here, welcome! This is a newsletter about the tricky-yet-powerful experience of longing I refer to as glamour. I recommend you peruse this brief introduction to glamour/the Fantasy Self as a concept before commencing with this edition of the newsletter.

When your parents divorce, God grants you many small consolation prizes. For me, television was one of them.

Growing up, my mom would hardly let us watch anything. Even Nickelodeon was off the table as a matter of course because its shows were vulgar, the worst of all possible sins.

To make friends in middle school, though, I needed to take part in more vulgar aspects of culture. I needed to watch the channels where people used bleeped-out swearwords. And to watch those channels—MTV or E! or VH1—I had to go to my dad’s.

Looking back on it now I think Dad’s strategy was really smart. Because I could watch those channels at his house—but he would always watch them with me.

Casually he’d come sit on the couch or linger in the kitchen, hunched over the newspaper so he could listen to it. Yet among the thrills and chills of Meet the Osbornes and Jackass and Fashion Police, there was one show he would not let me watch, only one:

The Girls Next Door.

He never said why. He’d always come in to change the channel on Sunday nights at 8, and re-runs, too. Because I longed for his approval, I didn’t watch it even when he was out of the house. I figured if he let me watch everything else, The Girls Next Door had to be pretty bad.

So naturally, when I was 28, my curiosity got the better of me and I watched the first four seasons in a compulsive, fevered binge that I can’t explain, even in hindsight. (Sorry, Dad. I tried.)

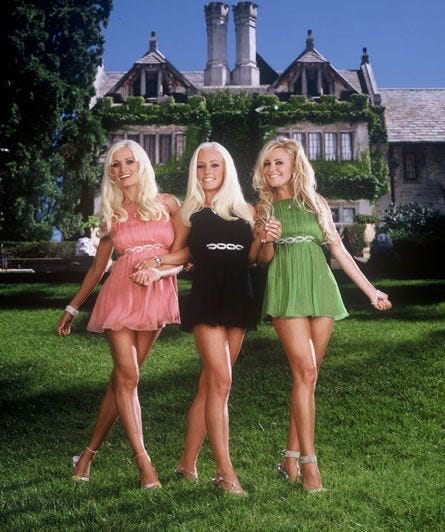

The Girls Next Door is a reality show about Hugh Hefner’s three platinum blonde live-in girlfriends, all of whom were about sixty years younger than he was. (I’m rounding to the nearest whole number but you get the point.)

The disorienting thing about The Girls Next Door is that you’d expect it to be raunchy and transgressive. Especially given how my dad felt about it. But while it was marketed as such, the actual content is almost entirely squeaky-clean.

It presents life as one of Hefner’s girlfriends like an especially anodyne episode of the Brady Bunch. To wit, there’s an entire episode—a fan favorite!—about a birthday party for Bridget’s dog.

One of the through-lines in the show is how badly the girlfriends want to be in the magazine, especially Bridget and Holly. In the pilot episode, Holly says in a talking-head interview that Bridget, who holds a masters degree, views becoming a Playmate as “the highest achievement in both body and mind.”

And this struck me, because they were already on a TV show! Wasn’t that a bigger deal than being in a magazine?

Why was becoming a Playmate so important to them?

We understand why the Playboy brand was appealing to men—that needs no explanation. But why did so many women look to Playmates as aspirational, glamorous figures, when cultural attitudes in America around nudity bring so much judgment and shame?

And why am I one of them…even though I’d never pose nude?

The Playmate: A Brief History

The first Playboy Centerfold/Playmate was Marilyn Monroe, whom some of you know is my ultimate Fantasy Self.

In 1949, Marilyn had changed her name, but she was still an auburn-haired, dirt-poor model just trying to break into Hollywood. She needed money, because her car had been impounded, so she agreed to pose nude for the first and only time, for an “art” calendar.

In most of the shots, her face is partially obscured, because she didn’t want people to recognize her. She signed the release Mona Monroe, for a payout of about $75. (That’s $995 in today’s money.)

I don’t remember how Hugh Hefner discovered these pictures, but he did, and he used them in the first issue of Playboy in 1952. He put a more recent picture of Marilyn on the cover, who by this time had become the platinum blonde supernova we all recognize.

He never paid Marilyn for the use of these pictures, nor did he obtain her explicit consent. On the back of these photos and Marilyn’s own skyrocketing fame, Hefner launched his brand. A brand that, like it or not, is up there with Coca-Cola and Ford Motors as one of the most globally influential American brands of all time.

In this set of photos from 1949 (which I am not linking to on principle—I just don’t think she’d like it), Marilyn embodied what became the archetype of the Playmate: The Girl Next Door.

She’s inviting and appealing, but not threatening. Beautiful, but approachable. Tantalizing, but not taunting.

When I think about Marilyn, I’m often reminded of something perceptive that Billy Wilder said about her: “Marilyn was never vulgar in roles that could have so easily become so. She always made you feel good when she was on screen.”

In other words, The Playmate embodies a kind of sexuality and beauty that’s wholesome1.

Young and soft and frisky, just like the bunny rabbit in the brand logo.

While Marilyn was unwittingly made a part of the Playboy brand, for the rest of the Playmates (at least as far as I know), it usually took deliberate effort. By the 1990s, when a young Holly Madison saw stars like Pamela Anderson on the cover, thousands of women tried out every year for the chance to be Miss September. They even had a short-lived competition reality show about the quest for the Millennium Playmate, the title of which I stole for this essay.

Evaluating the Glamour of the Playmate

Let me state for the record that Hugh Hefner was—at best—a gross old man. I’m not a fan of him.

So I’m not here to litigate Playboy’s legacy. And I’m not here to engage with the empowerment/objectification axis of posing nude.

Given that the genesis of the Playmate was a hurtful violation for Marilyn, who means a great deal to me…I have a pretty strong negative bias towards Playboy for that reason alone. And I haven’t even gotten to the numerous scandals and murders associated with the Playboy world.

It’s also worth remembering that people don’t necessarily know all that stuff when they first interact with the brand—Holly and Bridget and Sara didn’t. So just put all that tarnishing context aside for a second while we ponder this controversial question.

What I want to know is: could a Playboy centerfold—the image itself—be glamorous? And if it is, why is it glamorous to women, like Holly and Sara? Even though they’re presumably not who it’s for?

Here’s my evaluation:

Our informal rubric states that a glamorous image has to be graceful or effortless, either in actual fact or as the result of judicious editing. This is certainly true. Many people are surprised to learn that Playmates were, until very recently, not retouched. In the 2000s, according to Holly Madison, the “darkroom grace” mostly came in the form of specialized lighting, makeup artists2, and clever posing.

A glamorous photo must also convey mystery, which is literally the case in the sense that a Playmate isn’t famous. That’s the entire point. This gives her a blankness that makes for the perfect projection of fantasies of all kinds—including a fantasy that you could be like her someday. If she can be virtually anyone, why can’t she be me?

A glamorous image must also trigger a fantasy of escape or transformation. And I think some of these images do offer straight women like me something approaching a glamorous fantasy. But it isn’t about the story of the photograph. It’s about what the photo represents symbolically.

When I read Holly Madison’s memoir, and listened to her and Bridget’s podcast, I started to pull the thread. Because for Bridget, her fascination with Playmates started when she was only four years old3:

“My dad had the magazine subscription, so the magazines were kind of laying around. And even though I kind of knew that they…were not really for me to look at, I would sneak peeks at them. And I just thought that the girls were so beautiful in there. I didn’t see it as nudity or sexual or anything like that. I just thought, they’re so pretty, and I want to be like that someday.”

Holly says that “being a Playmate…was really like the height of what it meant to be a desirable, glamorous, sexy woman.” She was one of many who tried out for the Millennium Playmate in 1999 and didn’t make the cut.

Sara Underwood (2007 Playmate of the Year) first came across a Playboy magazine in college4. It belonged to one of her roommates. Sara says:

“I opened it up, and Jennifer Walcott was the Playmate. And I was like, this is the most beautiful girl with the most amazing body I’ve ever seen. Like, that’s all I remember thinking…how amazing to be that beautiful. What must that be like?”

The Fantasy, Revealed

And now, my dark secret (you knew it was coming):

All I’ve ever wanted was to be beautiful.

Because I’m smart, I’m not supposed to want this so badly. I’ve intuited that for a long time, even though people don’t say it out loud.

Being smart holds greater moral value in the eyes of most people than being beautiful, and you’re not really allowed to try to have both of them.

Worse still, it’s as if people can’t tolerate both qualities existing at the same time in the same woman. Which is why Marilyn, who died with approximately 400 volumes in her personal library, and whose dream acting role was Grushenka in The Brothers Karamazov, is still regarded as a bimbo. Even now.

I know in the grand scheme of things, this problem isn’t that important. And I know it’s an artificial dichotomy. But if I had to choose for myself between them, if I could only have one….

Dark secret #2: I’m ambivalent as hell about my intelligence. In fact you might even say that I have an inferiority complex about being smart. It’s one of my most painful insecurities, that when people (especially men) find this out about me, they’ll write me off as a bore or a bluestocking or something like that. I don’t expect anyone to feel sorry for me or think this is reasonable, by the way, it’s just something I feel sometimes.

I want the power that comes with being beautiful—even if it opens you up to frequent experiences of envy and resentment—because it’s a different kind of power than the one you get from being smart.

It’s a power that works on hearts and bodies, which like it or not is where most of us make our decisions—not in our conscious minds. In other words:

Beauty makes idiots of us all.

Beauty is the power that bamboozles the powerful.

It has razed nations to the ground, stoked eternal dissatisfaction, spurred generations of artistic flourishing and innovation, inflamed the dreams of the world’s greatest poets. Roughly half of all commerce is predicated on it.

When you’re a Playmate, you get to embody the power that hoodwinks the powerful. You get to be at the hypnotic center of it all for a moment in time.

Best of all, you get to withhold from everyone, because they can’t really touch you. That wonderful quirk of distance—unique to the still image—protects you. You remain indelible in time, eternally enticing and eternally out of reach.

And before the internet, Playboy centerfolds were more ephemeral, because they only existed on paper. Nude photos didn’t follow you around forever the way they do now.

The Centerfold Fantasy as it constellates for me is based on a subversion of the balance of power between this specific subject and its intended viewer.

He’s just some dude who can’t get laid.

You’re a symbol of Beauty Incarnate, and he can only possess you in dreams.

It’s a fantasy about becoming the subject of other people’s fantasies.

So yeah, I now understand why Hef’s girlfriends wanted to be Playboy centerfolds so badly. I hope that their multiple features in the magazine brought them immense joy and pride.

And I’m also glad that they each discovered that they had bigger dreams to pursue, and that posing for Playboy wasn’t their defining achievement.

What do you think of Playboy? Do you have a favorite Playmate or Playboy cover? I’d love to know. Leave me a comment with your answer!

And growing up a young Christian girl in America, let me tell you something—it never occurred to little Calvinist me that this aspect of myself could ever be seen as wholesome, natural, or welcome. Which is probably why I latched onto Marilyn so much when I was a tween and teen. She’d never judge me for wanting to (gulp) kiss boys!

Alexis Vogel’s work with Pamela Anderson in Playboy in the 90s is one of the most influential makeup looks of the 20th century. It continues to be the blueprint for millions of women. Vogel passed away in 2019, and when she died, Pamela Anderson decided to largely stop wearing makeup for public appearances as a display of grief for her dear friend.

excerpted from this episode:https://audioboom.com/posts/8352790-ep-1-the-prequel-getting-naked

excerpted from this episode: https://audioboom.com/posts/8481600-our-most-requested-guest-sara-jean-underwood

You grew up Calvinist too! No way!