Every week, Professor Mike and I argue about whether or not wolves have metacognition.

Professor Mike is one of the smartest people I know, despite his job title, and one of the things I appreciate most about him is that he will commit to the bit with me. I am deeply bored with rational or logical or strictly ‘real’ topics of conversation. I have many flights of fancy that must be entertained, including but not limited to:

My dad, at one point, may have been a spy.

Mathematics is a conspiracy theory designed to make little girls feel bad about themselves.

Change, paradoxically, only comes about with radical acceptance.

How tall someone appears to be is a matter of subjective opinion. People you like seem taller than they are.

My family cat, Muffin, is not just a cat, but actually an eccentric Anglo-Irish aristocrat who lives in a castle called Pear Caramel in the charming village of Sardines-Upon-Toast. Muffin can trace his lineage to the cat of Edward the Confessor and drinks only the finest cognac. He is both erudite and a little bit prim. He holds twelve doctorates. When engaged in his work as a Peer in the House of Lords, Muffin the cat focuses on interpreting obscure agricultural policies. His great crisis, his eternal MacGuffin, is not being able to find a sufficiently qualified chauffeur for his Rolls Royce Phantom. He has been trying to hire a chauffeur for the last six years.

All of these axioms, Mike is able to accept quite gamely, but he stops short of accepting that wolves have metacognition. And recently I’ve started to accept (reluctantly!) that he might be right.

The reason why I first believed wolves have metacognition—that they are aware of their own thinking, and know that they know—is because when you lock eyes with a wolf, your neck hairs stand on edge. But it goes beyond the adrenalized animal fear we have of bears or mountain lions. There is an uncanny recognition, an uncanny identification we have with the wolf that I don’t think we have with any other animal. It is this same instinctive kinship that drives so many people to kill these creatures for sport—a kind of compulsive repression, a frantic disowning of the uncomfortable truth that we, too, are apex predators…

…that we, too, are ancient and wild and brutal and excellent killers.

Anyway, what I’ve come to understand is that I am projecting a quality of myself onto the wolf. (So are the people who kill them for sport.) Professor Mike has of course known this all along and patiently waited for me to figure this out myself. I want wolves to have metacognition because I want to have something in common with them, the better to explain my deep fascination with them.

And projection is the final essential element of glamour. The other two are mystery and grace. I am drawing from the work of Virginia Postrel, who has initially made these definitions—but I am here to deepen and perhaps complicate them.

Glamour is Positive Projection. It’s also painful. How can this be?

One of the reasons why glamour intrigues me is because it stands in contrast to a particular trend in the culture. I think we are experiencing unparalleled levels of negative projection, where we ascribe our own worst traits to others as a means of disowning them. It’s completely pervasive, across the political spectrum. We are like the passionate trophy hunter who blames the wolf for all of his problems, setting leg traps for the ones we insist are evil, wrong, and horrible. I believe that’s Twitter’s business model—or whatever’s left of it, Elon!

But glamour is essentially an instance of positive projection. It’s about qualities we take to be positive rather than negative. Another person, or an image of a person, or occasionally a physical object (a car, a dress, a chef’s knife) is a chance for us to project a quality we wish we had (or had more of). We then build an alternative reality around this projection and turn it into a fantasy. We’re flying away. This phenonemon can still be leveraged in ways that are bad for us—glamour has dark manifestations, too. However, that only makes it more important to probe and understand. It is, as Virginia Postrel writes, the “illusion that contains the truth” about who you want to be. So it’s worth paying attention to where your glamorous fantasies take you. If you don’t, someone else might be able to exploit them without your realizing.

Glamour is an imagined escape from your current situation into the one you truly desire. This means that the effect it has on you is paradoxical. It creates both pleasure and pain.

Pleasure from your beautiful dream of an ideal life, triggered by some outside stimulus.

Pain from not having it yet. Pain of being in the here-and-now with boredom and loneliness and paperwork.

And I think this is one reason why glamour is uniquely compelling.

We like to think of pleasure and pain as sharply distinct. Humans are allegedly hard-wired to avoid pain. But then you see a picture of someone who embodies the qualities you most wish to have, seeming effortless and mysterious, and the pain/pleasure divide seems kind of arbitrary.

When I was little and saw that photo of Marilyn Monroe in the hair salon, it was the first time I can consciously remember those two sensations mingling with such an electric charge. Her beauty made my heart open like a flower, and it hurt me because I did not have it. And yet I loved to be hurt by it. Each opposing feeling only served to amplify the intensity of the other.

To me, that is the energetic signature of glamour that sets it apart from other fantasies trained on purely hedonistic sensations or pursuits. Convenience isn’t the subject of glamour. Neither is sex. Quoth Postrel, glamour doesn’t offer “a more reliable car, a thirst-quenching beverage, or an orgasm. It is not that literal.” Glamour connects us with our ideal states of being. We imagine ourselves as beautiful, powerful, beloved, desirable, adventurous, free, courageous, hyper-competent, famous. It depends on the person. Marilyn is glamorous to me, but she won’t be to everybody. The glamorous image, person, or object allows us to believe it’s possible to embody our desired qualities through escape or change.

I don’t think if our experience of glamour was merely pleasant that it would matter so much. But the fact that it heightens our awareness of the gap between who we want to be and where we actually are—there is magic in that.

Because I reject the idea that our fantasies are pointless and stupid.

I know it’s fashionable to say that. Perhaps as a reaction to the fanatical be-more-do-more-achieve-more energy of mid 2010s hustle culture, there’s now the “give yourself permission to rot in bed” school of reactionary thought. It’s cringe to want to improve yourself or achieve a goal. Nihilism is on trend and I understand why. The optimism required to have aspirations and goals—it can feel pretty insane sometimes, given how generally bad things are and how much microplastic is churning around in the belly of every sea lion. I used to find it deeply embarrassing that my inner world was charged with fantasies of beauty, belonging, and a closet bursting with beautiful silk dresses I could wear to drink Orangina in the park with friends. I used to think that wanting better for myself—wanting more, wanting anything at all—was preposterous and shameful.

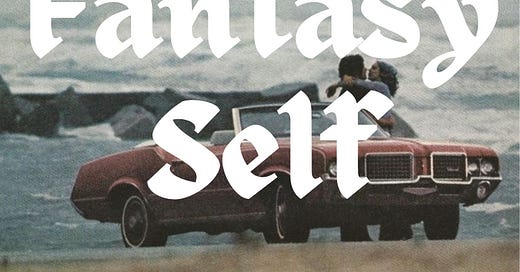

There’s an entire cottage industry on YouTube and Instagram of people who say they’ve decluttered the stuff they bought their ‘fantasy self.’ (This is where I got the name for the newsletter. I decided to reframe the term as a positive thing.) They’ve decided their Fantasy Self is silly1, and they’re going to let it run away from them. They’re no longer buying anything this Fantasy Self supposedly wants. Which is eminently reasonable. We are all buying too many things too often. But they’re also sometimes giving up on achieving the qualities the Fantasy Self has, too. Christ, how depressing it seems to just toss away this impractical, strange, beautiful guest in our house.

I say: what if your Fantasy Self is there for a reason? What if she loves you beyond measure?

And what if she’s already part of you?

Hannah Louise Poston has a great video about this. She brings a lot of nuance to the topic.